Sinclair ZX81: 30 years old tomorrow

by Tony Smith, reghardware.comMarch 4th 2011 11:45 AM

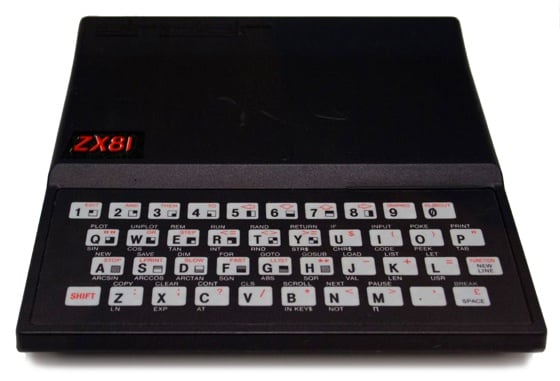

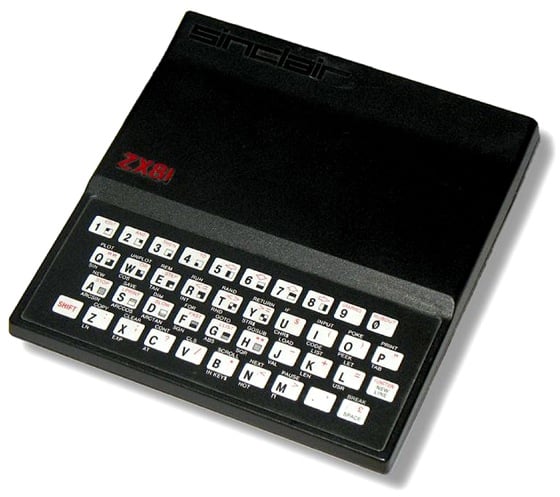

Tomorrow, 5 March 2011, marks the 30th anniversary of the arrival of the machine that did more to awaken ordinary Britons to the possibilities offered by home computing: the Sinclair ZX81.

While its successor, the Sinclair Spectrum, got the nation playing computer games, the ZX81 was the tipping point that turned the home computer from nerd hobby into something anyone could buy and use.

Sir Clive Sinclair would later say his Science of Cambridge company - later Sinclair Research - developed its first computers to make the money needed to fund other projects closer to his heart: the portable TV and what would become the infamous C5 electric car.

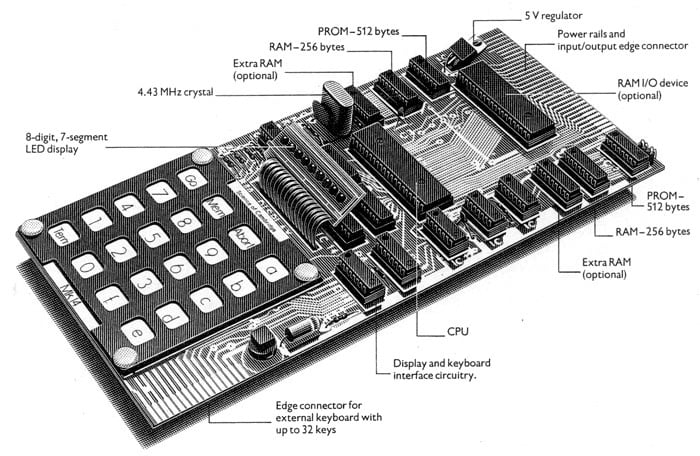

SoC's first offering was the MK14, proposed by staffer Chris Curry - who would later leave Sinclair to form Acorn and become rich on the back of the BBC Micro's success - as a DIY kit for electronics buffs.

Launched in 1978, the MK14 was basic: it had an LED array as a status and data readout. Very cheap it may have been, but it looked primitive when placed alongside the likes of the Apple II, launched in the US in the same year.

But the MK14 was sufficiently successful to warrant a follow-up, this time a machine that set the pattern for what was to come after, not only from Sinclair: a built-in Qwerty keyboard and a UHF modulator to allow a TV to be used as a display.

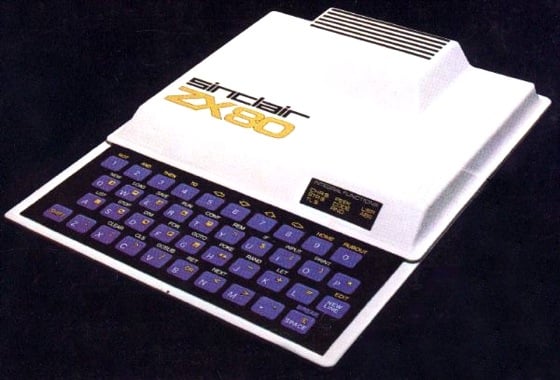

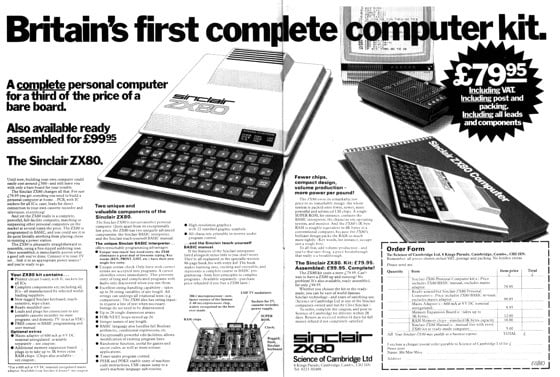

The ZX80 arrives... in pieces

Launched in January 1980, the ZX80 was, once again, a DIY kit. It has a Zilog Z80A processor, 1KB of memory and used a cassette recorder for storage.

But it had a key flaw - literally. Press one of the touchpad-style keys and the display momentarily blanked, as the CPU was diverted from maintaining the display to reading the keyboard buffer. Orders had been taken so SoC had to ship the product, but before the ZX80 was officially released work had begun on its successor.

A year on from the ZX80 debut, in January 1981, the ZX81 was still in development. But then the BBC came knocking on Sinclair's door. The Corporation was looking for a cheap home computer to tie in to a series of programmes it was planning to broadcast later that year.

Having seen the success of the Apple II, Tandy TRS-80 and Commodore Pet in the US, BBC senior management believed Britons needed to be quickly awoken to the personal computer revolution. It established the BBC Computer Literacy Project. A series of programmes would show viewers the potential of computers in their business and daily lives. The machine itself would get them directly involved.

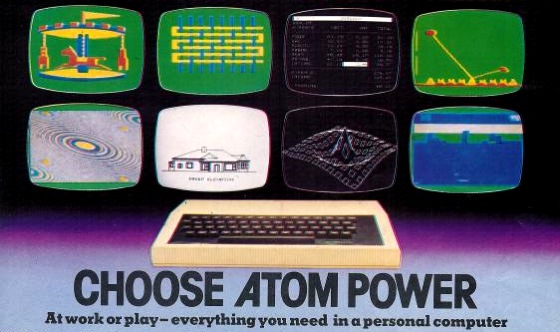

The BBC had initially selected Newbury Labs' NewBrain, announced in 1980. But Newbury failed to bid for the CLP, and the Corporation was forced to look further afield. Sinclair learned about the project and pitched the ZX80's successor. Chris Curry, now at Acorn, suggested a successor to its 1980-launched Atom.

Acorn antiques

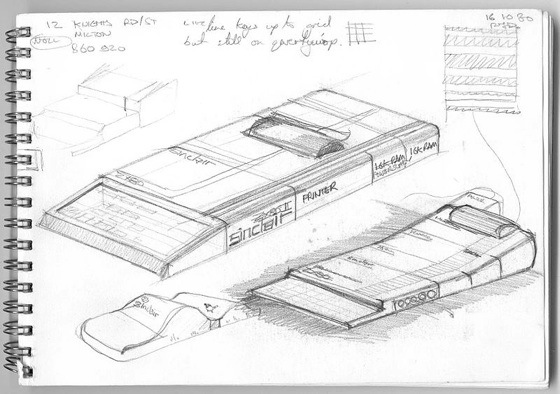

The natural rivalry of former colleagues forced Sinclair to push the development of the ZX81 hard. Already conceived as a follow-up that would be cheaper to produce than the ZX80 - it would use fewer chips - but contain dedicated video circuitry to prevent the ZX80's screen flash.

The ZX81 was developed by a team led by SoC's chief engineer, Jim Westwood. Its Basic interpreter and OS was written by John Grant and Steve Vickers at Nine Tiles, a company contracted by Sinclair for the ZX80's software. A bigger Rom chip - 8KB to the ZX80's 4KB - allowed Grant and Vickers to extend the new machine's functionality considerably, in particular floating point maths and trigonometry functions.

SoC's Rick Dickinson designed the iconic casing. The look was based on the ZX80, but out went that machine's vacuum-formed cover in favour of superior injection moulding.

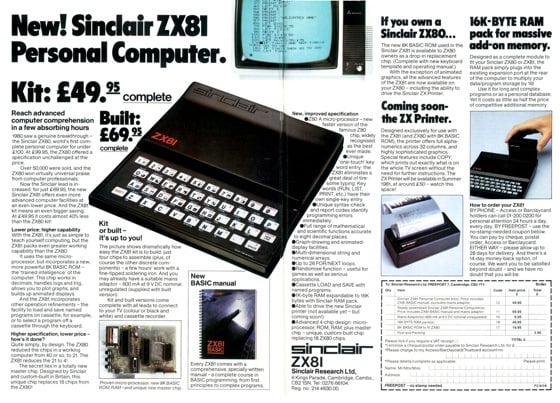

Once again, SoC used the Z80A CPU and equipped the ZX81 with 1KB of memory. A 16KB Ram Pack add-on would later be offered, and become the source of much annoyance - but hilarity to owners of rival machines - because its poor fit ensured that any movement could cause it to lose electrical contact, crashing the computer.

Sinclair had said the ZX81 would be out in the Spring of 1981, and, pushed hard, the development team managed to do so. The ZX81 was launched on 5 March 1981. Around the same time, Science of Cambridge was renamed Sinclair Research.

Selling the ZX81

The ZX81 hits the high street

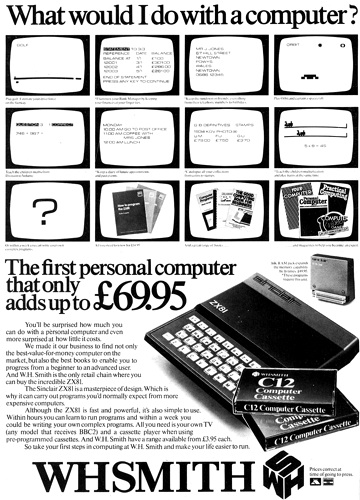

Like the ZX80, the new machine was offered as a £49.95 kit. But this time - and the use of a quality plastic casing suggests this was always going to be the case - it was also sold pre-assembled for £69.95. Both versions were made by Timex, which would later license the design for the US market, where the computer would debut in the States as the Timex 1000.

At such a low price - though still beyond the reach of many a computer-keen kid at the time, this reporter included - Sinclair sold truckloads. He was helped in no small part by the retailer WHSmith, which, by offering the machine in its shops, put it in the way of far more ordinary buyers than ads in early computer magazines would have done.

WHSmith had an exclusive for six months, and then other high street retailers jumped in too. Sales soared, Sinclair became a household name and even richer as his company's fortunes rocketed.

More importantly, a new consumer electronics category was born, and the UK home computer market was defined and led by UK companies. That would change, but not for a few more years. But by then thousands of schoolkids had had their first taste of computers, programming and, - crucially - games. Their hunger was not sated... ®

Thanks to the many ZX81 and Sinclair fans who provided the ad scans. Special thanks to reader David Corbett

Original Page: http://www.reghardware.com/2011/03/04/sinclair_zx81_anniversary/print.html

Shared from Read It Later

Thank you so much for sharing.........

ReplyDeleteOffset Printing Sydney

Good old WH Smith. I dread to think how many hours of productive employees' work were lost by their having to police the micro displays and stop kids (not me, oh no indeed) writing programs that produced, er, unorthodox messages...

ReplyDelete